The topic of Pata Khazana became a very thorny and sensitive issue from the get go. Qalandar Mohmand, who casted doubts on the authenticity of Pata Khazana in his ‘Pata Khazana fil Mizan’, writes that Pashtun writers from Afghanistan told him that casting doubts on the authenticity of Pata Khazana is against the national interests of Afghanistan !. It also became a matter of ‘national interests’ for certain Pashtun writers of Pakistan. They rather angrily and rudely criticised the critique of Qalandar Mohmand, and even resorted to personal attacks against him. The Tajik ethno-nationalists poured oil on the fire by taunting and mocking Pashtuns for inventing history through Pata Khazana.

The original manuscript of Pata Khazana

Abdul Hai Habibi discovered Pata Khazana in 1943, and until his death in 1984, he never produced the original of the manuscript for examination and testing by historians. This made the doubters of Pata Khazana even more doubtful. However, the original manuscript of Pata Khazana does exist and is placed in the National Archives of Afghanistan, Kabul. At the end of the book there is a note in Farsi by the scriber stating that it was scribed in 1886 AD by Muhammad Abbas Kasi in the Quetta city at the request of Muhammad Akbar Khan Hotak of Kandahar.

Note that Quetta was part of the British-Indian empire in 1886.

Professor Sial Kakar (a Pashto author and poet from Quetta) reported that he and Habibullah Rafi (a Pashto writer from Afghanistan) visited the National Archives of Afghanistan in 1987 and examined the original manuscript of Pata Khazana there. He writes:

“Based on my past research dealing with Pashto manuscripts and after a thorough examination of the book I can say with confidence that the manuscript was scribed nearly a century ago. From historical documents we know Pata Khazana was written by Mohammad Hothek. A second copy was scribed for Sardar Mehrdil Khan Mashreqi of Kandahar and later Mohammad Abas prepared yet another copy of the book which we have at our disposal that is preserved in the National Archives in Kabul.

This copy was scribed on a foreign made yellow paper with black ink. We can deduce that it was written in a mixture of Nastaliq and Naskh scripts. The writing of all the pages is contained in a single-lined rectangular boundary but it does not have any embellishments. On some pages the stamp of the Literary Society of Kabul can be seen.”

After studying the manuscript I can say that the script and paper used in this copy, scribed by Mohammad Abbas, matches the style of writing of those Pashto manuscripts which were scribed by Pashtun calligraphers a century ago. We see this style of writing in different Pashto books preserved in various libraries.”

Georg Morgenstierne was not fully convinced of the authenticity of the Pata Khazana

Georg Morgenstierne (1892-1978), a specialist of Indo-Iranian languages, and author of “An Etymological Vocabulary of Pashto”, did not buy it. He expressed his doubts about the authenticity of Pata Khazana because of the “grave linguistic and historical problems” in it. In his article in the “Encyclopedia of Islam”, he writes:

The letter sent by Georg Morgenstierne to Alessandro Bausani (an Italian orientalist of Arab and Persian studies), reveals that the former was convinced that some parts of Pata Khazana were likely fabrications of Muhammad Hotak while some parts of it were likely authentic oldest Pashto texts. The poetry of Amir Kror Suri was bothering Georg Morgenstierne which he found “suspiciously too modern”. But in the same letter, he also stated that “One can believe in the authenticity of Pata Khazana as the work of Muhammad Hotak”. He speculated that Muhammad Hotak might have invented some of the poetry himself out of patriotism.

Some of the critical points raised by Qalandar Mohmand about Pata Khazana

Qalandar Mohmand dismissed Pata Khazana as a forgery of modern times on the basis of some errors and anachronisms.

1- Muhammad Hotak, the compiler of Pata Khazana, writes, “I started to write the book on 16-Jamadi-al-Sani, 1141 H, and it was “Friday”.

Qalandar Mohmand, a well-known Pashtun research scholar, literary critic and Pashto poet, pointed out that on 16-Jamadi-al-Sani, 1141 H, it was “Monday” not “Friday. A slip, which someone of later times would make.

The fact that on 16-Jamadi-al-Sani, 1141 H, it was Monday, can be verified on this website : Hijri Gregorian Date Converter – Islamic Calendar (searchtruth.com)

Abdul Hai Habibi responded by saying that it must be a scribal error by Muhammad Abbas Kasi who copied it in 1886. The latter must have written 16 instead of 6 by mistake. It was Friday on 6-Jamadi-al-Sani, 1141 H.

2- The 12th century poet “Khkaronday” of Pata Khazana, a courtier of Shahabuddin of Ghor, has used the word Attock in his poetry for the river Indus. Qalandar Mohmand writes that there is no historical proof that river Indus has ever been referred to as Attock in 12th century.

It was Akbar who first coined the term Attock. He built and named the fort Attock Banaras to rhyme it with Katak Banaras (a fort on extreme east of his empire).

3- Qalandar Momand writes that the facsimile of Pata Khazana has letter “ځ” which came into being after the creation of Pata Khazana. Qalandar Mohmand, citing Abdul Shakoor Rashad, writes that the present shape of the letter “ځ” of Pashto Alphabets, has been created by Wazir Muhammad Gul Khan Momand in 1936. Thus Pata Khazana was written after 1936, not 1886. On this basis, Qalandar Mohmand also dismisses “Tazkirat-ul-awlia” of Sulieman Mako as a forged document which also contains “ځ” letter.

However Abdul Shakoor Rashad (who was cited by Qalandar Mohmand as authority) later stated that he made a honest mistake and that the letter ځ does appear in some sources written before 1936.

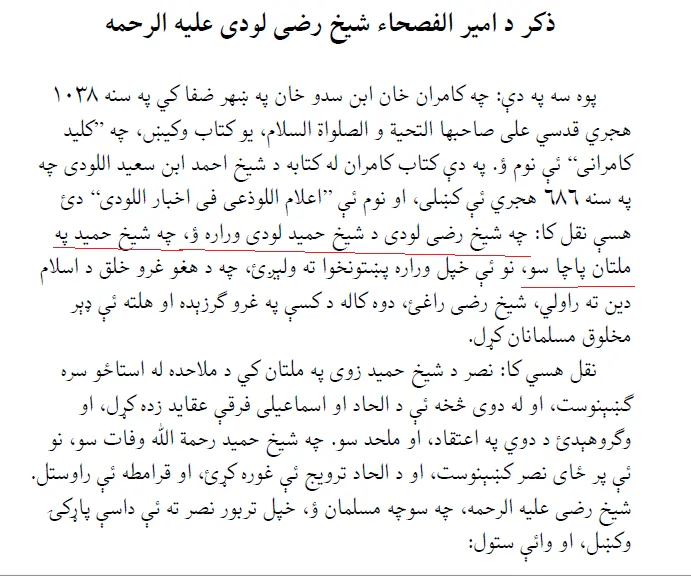

Lodi Pashtuns did not rule Multan in 10th and 11th century AD

Tarikh-i-Farishta, a 17th century source, says that Multan was ruled by an Afghan (Pashtun) “Shaikh Hamid Lodi” in 10th century. Whoever wrote Pata Khaza, was borrowing the information about Shaikh Hamid Lodi from Tarikh-i-Farishta and turned nephew of Shaikh Hamid “Lodi” into a Pashto-speaker and Pashto poet.

It has been demonstrated by H.G.Raverty in 19th century that Lodi was miswriting, and Qasim Farihsta mistook Lawi (لوي) for Lodi (لودي). The assertion by H.G.Raverty is corroborated by various 10th century contemporary sources. Masudi, Istakhari, Iban-i-Hawkal and Al-Madqisi all says that the rulers of Multan were Arabs, and they were descended from Usman bin Lawi bin Ghalib, an Arab of the tribe of Quresh.

Masudi visited Multan in 912-913 AD and informs us that it was ruled by Qureshi Arabs, descendants of Usman, bin Lawi, bin Ghalib.

Ibn-i-Hawkal completed his work in 977 AD, writes that Emir of Multan was a Qureshi :-

Hudud-i-Alam of 982 A.D, also informs us that Multan was ruled by a Qureshi :-

Al-Madqisi visited Multan in 985 A.D and reported that Arab rulers of Multan acknowledged Fatmid rulers of Egypt as their Caliphs (i.e they were Qaramites).

There is no evidence that Shansabani rulers of Ghor were Pashtuns

According to oral traditions recorded by Makhzan-i-Afghani (written around 1613 AD), a number of Pashtun tribes are descended from a Ghorid Prince Shah Hussain who married a Pashtun woman named Bibi Mato in bygone times. Makhzan-i-Afghani describe that Ghorid prince as a non-Pashtun and because of that, his progeny identified themselves as Pashtuns matrilineally through Bibi Mato and her father Beit, thus are referred to as either Mati or Beitani tribes. The same source also records a tradition that Pashtuns initially inhabited Ghor and from thence migrated to Suleiman mountains. Thus some connection of Pashtuns with Ghor and its people (the ones inhabiting Ghor before Mongol invasions) is not an invention of Pata Khazana.

There is no evidence that rulers and people of Ghor spoke Pashto in the times of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi and Muhammad bin Sam Ghori. It is evident from Tarikh-i-Bayhaqi that they were not Farsiwans either.

Amir Kror Suri, son of Amir Pulad Suri, is an 8th century Pashto poet from Ghor according to Pata Khazana. As per the creator of Pata Khazana, Suri was family name of the ruling dynasty of Ghor.

However, Suri was not the family name of the ruling clan of Ghor. The best authority on lineage of rulers of Ghor, is Tabaqat-i-Nasiri written by al-Siraj Juzjani who spent his childhood in the harem of a Ghurid princess. He informs us that the ruling family of Ghor was called Shansabanian with reference to their paternal ancestor Shansab.

Tabakat-i-Nasiri does not refer to Amir Pulad as Suri. He is being referred to as only Shansabani and Ghuri.

“Suri” was a Malik of Ghor in 10th century. His son was Muhammad ibn Suri (Muhammad son of Suri), who was contemporary of Mahmud of Ghazni [Tabaqat-i-Nasiri].

Al-Utbi, secretary of Mahmud Ghaznavi, mentions him as “Ibn-i-Suri” (son of Suri).

The only other person in the family tree of the Shansabanis who had name of Suri besides Amir Suri, was Saif al-Din Suri. The ruling family is never referred to as Suri in Tabakat-i-Nasiri.